There was a workshop in my office hosted by the JICA (Japanese) volunteers on Friday. When the visiting volunteers left, they left two chocolate fudge brownies (imported from Japan) on my desk. I wanted to save them until Tuesday to eat in lieu of birthday cake, but that didn’t quite happen. I had one for dessert Saturday evening, and the other before breakfast Sunday morning (I know, I know …). They were incredibly delicious. Even without being in Ghana, I know they would come close to some of the best I’ve ever eaten.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Just Like Sunday School

One of the things I love about Ghana is that all meetings start and end with a prayer. Northern Ghana is a very peaceful mix of Muslim and Christian, so these prayers may be to either Allah or the Christian God with which I am more familiar. Either, or, the entire group of meeting attendees joins together in prayer. I love this idea. There are many times where I have almost asked for a prayer in my work meetings. Attending a minimum of three church meetings a week, which I have been doing way longer than I have been attending work meetings, it is somewhat habitual to do so. It is needless to say that I have been in many work-related meetings in Canada which could have benefited from some structure or guidance from a higher power. Nevertheless, I find that the process of getting someone to pray in a meeting is very amusing. Not the way that it is done, but rather, that it mirrors the exact same process that occurs when teaching Sunday School.

Meeting Chair: Can I have a volunteer for prayer?

<Silence. People look down or out the window.>

After some silence or more prodding by the chair, someone usually prays, or volunteers someone else to pray.

Friday’s dialogue went like this:

Director: Can I have a volunteer for prayer?

<Silence>

Director: We need to start this meeting, so we need a volunteer to prayer.

<Silence>

Director: Remember, you receive more blessings when you pray. Nobody wants blessings?

And then someone eventually rises: “Let us pray.”

Every time, I sit their smiling, or perhaps more accurately grinning, while chuckling in my head. Whether it is a room full of giggling 8 year olds, or senior government officials, getting someone to say the opening prayer is always a challenge.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Babile Research Farm

Lawra District has a research station, located in Babile. This is separate from any demo plot or field school, and is strictly for research purposes. It is run by Mr. Dangana, DAO Crops, who is one of the most enthusiastic and energetic individuals I have met in Ghana thus far.

In talking with him about what makes a good innovation or technology, he emphasized that it needs to be sustainable, flexible and easy to adopt, and not radically different from the way current things are done, but different enough to make impact.

There are currently four experiments in progress at the research station.

1 – Early Crop Selection

In partnership with the Savannah Agricultural Research Institute, they are testing 18 varieties of “Very Early” and “Early” maize for suitability in Northern Ghana. “Very Early” varieties will yield mature produce in about 2 months, while “Early” in 3 months. This would give the farmers an opportunity to get food on the table and/or produce to market earlier to get the cash flowing, while waiting for their “regular”, high-yield/quality crops to mature.

Each experiment is divided into 4 plots, with 4 replicates each. They are planted in a randomized block to try and spread each variety over the entire land area, incase there are specific areas in soil imbalances or infertility.

From these results, they will take the best performing varieties, and then give them to farmers throughout the district to test. Even within Lawra district, the soil and climate conditions vary greatly, so testing in multiple regions is required.

2 – Fertilizer Application Regimens

This set of experiments is to assess the economic value of using different fertilizer applications. In essence, the question is: Does the increase in yield received with one, two, or three fertilizer applications in the growing season result in enough profit to offset the increased cost of fertilizer application?

Next year, the experiment will be expanded to include additional factors such as compost, and tillage.

3 – Crop Rotation for Soil Fertility

It is well known that crop rotation is necessary to ensure continued soil fertility. This experiment was focused on trying to chose crops which compliment each to the extent reliance on fertilizer can be dropped while maintaining yield/profit levels. Specifically, this experiment was looking at using legumes (soybeans), alternated with maize. This experiment will be continued over the course of a couple of years to realize the full impact.

4 – Sesame for Income Generation

Sesame is being grown to assess growth, yield and market potential in Northern Ghana, with the interest of introducing this to farmers as an additional income generating crop.

Not Quite an Experiment …

In his visits to the Research Farm, Mr. Dangana observed that the neighboring farmer is struggling with his cowpeas. Cowpeas are very sensitive to the timing of their planting. They must be planted such that when they go to flower, it is not during the heaviest rains of late August and early September. The flowers only open during mid-morning, and will be easily damaged by rains, or insects that come with the rains. Furthermore, if the plant is left in flooded fields, the flower formation will be stunted. In his conversations, it was realized that the farmer just plants when he thinks is “right”, which, given the condition of his crop, was wrong. Mr. Dangana would like to convince the farmer to allow him to help him next year. His proposed experiment would be to plant one-third of the field early enough to flower before mid-August, plant one-third to flower after mid-September, and then allow the farmer to plant the remaining third when he feels is appropriate.

Graduate School

Mr. Dangana really wants to go back to school and complete his M.Sc. in Agricultural Science (the specifics were over my head). However, he does not want to do it in Ghana. He explained that while you can do a Master’s in 2 years in most countries, it can take up to 6 years in Ghana. Why? The professors delay your experiments and try to control too many things. So, while I complained about the couple extra months and hoops to jump through while finishing my M.Sc., I guess it wasn’t that bad after all. While he wants to go abroad to complete his degree, Mr. Dangana’s intent is to return to Ghana with new research methodologies, new ideas for experimental design, new crop technology and even more passion for what he does (if that is possible). Ideally, he’d love a Ph.D. as well. But, given the financial realities of going abroad, he may just end up staying in Ghana for his M.Sc.. After potentially 6 years, he says he’ll be too broke to even consider a Ph.D.

More Things to Come

This week, Mr. Dangana approached me and Mariko about helping him design his next round of experiments, both for the research farm, and for another project he has found land / willing farmers to use. I suggested the idea of comparing some of the natural fertilizers and pesticides identified in the Farmer Innovation Challenge against commercial products. He liked the idea! He presented his other project to me very quickly: introducing new vegetable varieties for irrigated dry-season farming. I quickly noticed a gap in appropriate experimental controls, and talked to him briefly about it. I loved his response: “This is why I wanted to use more brains!” He is going to write up a more detailed approach and plan, and then the three of us will work on making sure the objectives and experimental design are appropriate. A little bit of scope creep for my placement, but I’m actually kind of excited about it.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Contract Signing

Today I went out to the field with the Lawra AEA, the District Director, MISO (Management of Information Services Officer) guy, and the Extension Director to help them get the farmer contracts for the Expanded Crop Program (aka Block Farms) signed. These contracts should have been in place at the beginning of the program, but alas, they were just being done now.

As I’ve previously described, Block Farming is an interest-free agricultural inputs loan program. Services (e.g. plowing, harrowing) or inputs (e.g. seed, fertilizer) are provided to the farmers to enable them to get a farm going. Specific unit rates per acre were set by the ministry. The farmer must then pay this back, either in cash or in kind within one month of harvest. The services provided to the communities we visited totaled GHC154/acre (plowing, harrowing, seed, fertilizer and shelling). A fixed price per bag of maize has been set by the Ministry such that an in kind payment would be 3.5 bags. The farmer must then make the decision whether it is better to pay in cash, and hope he can sell the 3.5 bags for more money at a future date.

Many farmers had concerns about whether or not the rates were fair. The rates were determined using the assumption that a farmer would yield, on average, 10 bags per acre. What if they don’t get that yield? Will they be able to turn any profit? This is where the concept of the Harvest Committee was introduced. A representative acre is to be selected by each community for threshing and assessment by the Harvest Committee. Based on the yield, the Committee, which is made up of a combination of agric officers and representatives from block farms in an area, will evaluate the harvest and whether or not the rates were fair. They may be room for an adjustment if necessary. A harvest watchman needs to be employed by each block farm to ensure that no crop was stolen or added during between harvest and assessment. The watchman will receive a small salary from MoFA for his work. The farmers were told that if their yield was poor due to their own actions (e.g. not weeding, failing to apply provided fertilizer, etc.) then no loan adjustments would be made. If their crops were affected by things beyond their control (e.g. flooding, drought, etc.), then they would be eligible for adjustment or relief. Some of the passing comments, of both farmers and agric officers, made it seem like some farmers were already taking and “hiding” some of their harvest to make it look like they were not profitable. My thoughts, “And who said farmer were ignorant/lazy?”

At every location, the farmers also expressed concern that they received their inputs late in the season, and therefore the block farm crops are behind. This is true. It was the first year running the program, and it was delayed getting off the ground. MoFA staff reassured that this would be taken into consideration in assessing harvest and loan adjustments. Again, skepticism was received from the farmers.

Additionally, there were some farmers who experienced massive flooding and crop failure. The MoFA staff reassured the farmers that this has already been documented, and the appropriate reports filed, and these loans would be forgiven. The farmers did not seem entirely convinced.

Nevertheless, they appeared willing to sign the contract. Perhaps because they really didn’t have a choice at this point.

As we set out sign the contracts in the first community, we divided the people into queues with each officer who would fill out the form on their behalf. The point was then raised that the spelling of their names should match those that were already on record (I never really thought about the fact that if you are illiterate you probably don’t know how to spell your name). The process was a little chaotic, but we managed to create a system whereby the farmers would come to the AEA, who would write their name on a slip of paper with the spelling that he uses in his records. The farmer would then take their name to one of the other officers who would complete the form. I would then bring the inkpad over, and the farmer would sign via thumbprint. I then collected the forms, and had them signed (thumbprinted) by the farmer group president for a witness signature.

As we were headed to the next community, I suggested that while the Director and AEA were explaining the contracts to the group, the rest of us could fill in the loan information on the forms, and put in the farmer’s names based off of the records. That way, we could then just call each person up one-by-one and get their thumbprint signature. We implemented this process, and our visits to the remaining communities went a lot more smoothly.

I found it kind of humorous that in our last community there were a few folks who could sign their name, but elected to use their thumbprint anyway. Their rationale was that someone could forge their signature, but not their thumbprint. True enough.

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Tro-Tros

‘Tro-tro’ is the catch-all term for pretty much any licensed passenger vehicle that isn’t a bus or a taxi, ranging from comfortable and only slightly crowded minibuses to customized, covered trucks with densely packed seating, a pervasive aura of sweat, and bugger all chance of finding an escape route should you be involved in an accident’ – Bradt Guide, pg. 68

Too Good To Be True

As much as I want to sleep in (despite the fact that I get up hours later than most Ghanaians anyway), some Saturdays I feel must get up “early” and head to Wa for internet and fruit. The weekend of this story (and the one that follows) I wanted to take the MetroMass bus. A little safer, cleaner and more comfortable. So, I headed into town at 07h40 to catch the bus that would leave at 08h00+/-30min. It hadn’t yet arrived, so I started to try and find a place to sit in the shade until its arrival. As I did so, a man asked me if I was headed to Wa. He had a tro leaving shortly. I really wanted to take the MetroMass; I wasn’t up for potentially sitting next to a chicken or goat. However, he was insistent his tro was better than the bus. This is one of those instances where I did judge him by his appearance, not just of him, but also his tro. They both were clean and seemed to be in good repair.

“Are you going to stop 100 times along the way?” I prod.

“No, we are going straight to Wa and will only stop in Jirapa”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes”

“Really sure?” I’m sure he is internally laughing at me, as much as I was. Really, a tro that won’t stop 100 times. Ha! “And you’re leaving right now?”

“Look, we’re just finishing tying the load”. Ok, I give him his GHC2.10 and get in. The remaining passengers settle, and five Canadian minutes later the door seamlessly slides shut (looking good so far).

We started down the Nandom-Jirapa road and I realized that the tro isn’t rattling, and seems to be driving pretty smooth (another point for this tro!). And then I noticed the bars on the windows. Crap, no escape route in case of accident! But I quickly did a mental check and yes, I had my Swiss Army knife. The screws didn’t look like they were in too tight so I should be able to unscrew the bars if need be. But he was actually a good driver, so I tried to relax my mind.

The music started, something that I would describe as Ghanaian BackStreet Boys, and at a reasonable level too. The teenage girls in the back seat started to sing quietly along with the music. They were actually pretty good.

We’re almost to Jirapa and we hadn’t stopped yet, this is pretty good. I then realized that it’s pretty quiet. The goat in the back had fallen asleep; rare, and extremely amazing. We exchanged a few passengers and carried on our way. I was then struck with the thought: goats don’t fall asleep in tros, what if the goat died? I laughed at myself for being concerned, and then let the thought go. Even if he had died, there was nothing I could have done about anyway.

As we approached Wa, the goat woke up; I was secretly relieved that he was not dead. In the tro yard, I disembarked, quite amazed at how wonderfully perfect that tro ride was, grabbed some bananas for a hobbit breakfast, and headed off to the internet cafe.

Living On A Prayer

Note: Parents and grandparents should probably skip this story.

After a great day of internetting and shopping, I made it to the tro station by about 4:10pm. I wanted to leave Wa no later than 4:45pm, 5:00pm at the latest. That way I would be in Lawra before dark. Furthermore, I could tell there was a big storm brewing. There was no way I wanted to be in a tro, on a horrible dirt road, in a torrential downpour, in the dark. Well …

Let’s just say my “too good to be true” ride, had to be balanced out by the opposite experience.

There was one tro to Lawra just pulling out as I got to the station. There were just a bunch of empty spaces in the line, but a lot of people waiting around. I started asking where they were going, Babile, Jirapa, Hamale … ok, all these mean I can still get home, or at least closer to home. One tro to Jirapa started to fill up. I tried to get on, the conductor actually pushed me away and said no. I was mad. After arguing (my theory was get to Jirapa, and grab something else to Lawra). He said I had to go to the ticket window and get a ticket. I have never had to do that before. There was a bunch of us sent to the window, so we went and waited … eventually they got around to selling tickets, but of course, there was no tro to Lawra. This other girl and I shared a “yeah right” and proceeded to go back tros and started harassing drivers. It was now past 5:00pm, and I was getting nervous.

I saw some of the Babile and Hamale people starting to get on a tro. I ran over and asked them if they were going to Lawra. Of course they were, since Lawra is in between the two towns. I think they were about to say they were full, so I proclaimed that “I need to go to Lawra now”. The conductor and the driver exchanged a few words in Dagaare and then shoved me in the front seat, I would sit next to the driver. At least I was going.

Or was going to be going.

Another 45 minutes passed with us all loaded in the tro before we took off. I’m not entirely sure what was going on, I was focused on trying to mentally cool off without drinking water. I already had to go to the bathroom, but had no idea when I would reach home. I was also trying to ignore the fact that to my left, the sun was starting to slip lower in the sky, while on my right the clouds were billowing higher and higher while getting darker and darker.

Seconds before I’m about to lean out the window and buy FanIce (ice cream), we take off. I settle in, precariously balancing myself on the edge of a too small seat, while trying to give enough room to the gear shift while trying not too smoosh too much into man sitting next to me.

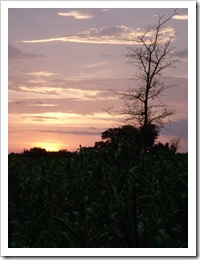

Heading out of Wa, I enjoy what was actually a very beautiful sunset in the west, accented by tremendous lightening on the other eastern horizon. While chiding myself for being an internet glutton and not leaving Wa earlier, I enjoyed the beauty in these few moments, knowing what would be next.

Just as the sun slips below the horizon, the skies open. Within minutes, the tro becomes akin to what a Toronto subway car does when it enters into St. Clair West Station on a hot, rainy rush hour morning in July. (For the non Torontonians this means sauna-like, completely fogged, very crowded, ew!). To compound this problem, I quickly realized, as did the driver, that the defrost (or is it defog in Africa?) doesn’t work. He pulls out his hankie, and proceeds to drive with one hand, while wiping the windshield with the other.

“Please slow down, please slow down,” I’m pleading in my mind. It works, he drops his speed to 55kmh (from 70kmh). A little bit of defrost comes on, the wiping is seeming to work well. His cell phone rings.

“Don’t answer, don’t answer.” This time the pleading doesn’t work. I think it was at this point I fully internalized the fact that I’m sitting in the front seat of a flat-fronted vehicle. We hit anything, I am dead. And while I’d offered a few little prayers at the outset of my journey, it was around this point that I lapsed in full on pleading for my life. The road was flooded. It was raining so hard that visibility had dropped drastically. And then I saw lights in front of us, the gap between us and them quickly narrowing.

Another prayer. I quickly ran through the list of people I emailed that day; I think I got everyone who was of utmost importance to me. I hoped that I had explicitly wrote in the emails to my family that I loved them. The driver noticed the lights too, and applied the brake. I think we were both hoping there was enough traction.

Fortunately we slowed in time. And then he turns on his signal light. Passing was definitely not a good idea, but he does so anyway. As he starts to speed back up to 50kmh, I see more lights ahead of us. This time they were stationary, and slightly to the right. But the vehicle was also moving towards the right.

“I’m going to be sheared in two!” my mind screamed. Well, since I’m here to tell this story, I wasn’t, but please don’t let that diminish the terror I felt at that moment. We stop in front of the vehicle. The unwritten rules of the tro world seem to be: you see a stopped tro, check to see if they are ok. We were doing just so. The other driver came up to us and said that they were just stopped because it was too bad to drive (why wasn’t I on that one?). It started to rain even harder, if that was possible. Our driver turns off the engine.

Another prayer, this time of thanksgiving. I resume breathing.

A few short minutes later, he starts up the tro again. Sigh.

Another prayer. I hoped he would drive slowly this time.

We pull back onto the road, precariously creep along, a little slower than before. As we reach Jirapa the rain stops. This is particularly fortuitous because at Jirapa, the pavement also stops. After a few stops through the town, we head out into the dark yonder. I’d heard the side road from Jirapa to Babile was pretty bad. I can now attest that this is not just a rumor.

We get to a town and he turns off the engine. At this point I’m half asleep, trying to ward off the rumblings in my lower intestines, and fighting off a heat and anxiety induced headache.

I try to read the sign out the window. I was pretty sure this wasn’t Lawra, but you never know, I felt delusional at this point. Ok, Babile. Sigh. Almost home. I close my eyes. The driver then starts to talk to me.

“I am going to chop [Ghanaian for eat]”

Seriously? Babile is 21 km from Lawra. I was so angry, but quickly rationalized that he was probably Muslim, and fasting (it was still Ramadan), and that since the sun had been down for a few hours by this point he probably needed to eat.

“Ok, but will you come back and go to Lawra?”, everyone was getting out of the tro.

“This is Babile. I need to chop,” as he makes motions for eating.

Yeah, ok, dude, I know it’s Babile, and I know what chopping is, but are you going to get back in and drive me to Lawra? We came to a mutual understanding that he was going to go and chop, and then come back and drive on to Lawra and Hamale.

I was too tired to even get out of the tro, and at this point, starting to feel sick. I just sat in my seat and closed my eyes, attempting to sleep. I heard people talking about me. Sigh, “nasa po”. I just feigned sleep.

Once we got going again, it quickly became evident that while it was no longer raining, the rains had definitely passed through. Fortunately, I now had the entire front seat to myself, and sat there half sprawled, staring out the window.

We finally arrived in Lawra and as I started to get out, the driver and the two ladies sitting behind me try to stop me. They wanted to know where I was going, and where I should be let off at. I explained to them that I live only 5 minutes away, and it was ok. They were continuing on down the Hamale Road, and I live down the Nandom Road. After relentlessly asking if I would be safe, they let me go. Quite frankly, I just wanted to get out of the tro. I was also a little annoyed that they were concerned for my safety at this point in the journey. I assured them it would be ok, and I started to walk home, with Britney’s Circus, playing from the downtown record store (a detail I feel compelled to sure, although I’m not sure what it adds to the story). As I left the town centre I pulled my flashlight out of my bag and turned it on, only to realize that the batteries were dying. I turned it off, making the decision to use it only if I heard or saw any approaching vehicles. The road was straight, paved for most of the way, and in remarkably good condition for Ghana. However, as fate would have it, just as I turned it off, I tripped in one of the rare potholes on this road. In an effort to save either my face or my avocadoes (not entirely sure which one), I put out my hand, only to cut it on the jagged pavement. Sigh. At this point I abandoned any hope of making myself a late dinner and just wanted to crawl into bed. Just another kilometer, if even. A UN truck passed me and turned into the Guesthouse. Just another 200 m, and I cross the road about to head across the little field in front of my place. A moto pulls up to me. Seriously!? Just leave me alone, I’m thinking. The fellow introduces himself with his name, and his UN project. To further validate himself, he points ahead and says that the rest of his team is in his truck. (This is thoroughly appreciated!). He just wanted to make sure I was ok, since we were now at the edge of town, and he didn’t want me walking in the dark. I was comfortable enough to point to the smaller guesthouses where I live and to tell him that I was now home. He told me he was relieved, and just wanted to make sure I was safe in Ghana, and heads into the big guesthouse where he was staying.

I got home, rehydrated, ate one of my avocadoes, and climbed into bed, falling into an immediate and deep slumber.

Cheated

On another journey to Wa …

As we approached Wa a young lady and her son got off. The driver offloads two bags of rice from the roof for her and demands more payment. I could tell something was not right, the lady looked like she was going to cry. Others on the tro were staring out the window in disbelief and whispering quietly. I could tell this argument had something to do with money, but my Dagaare language skills are virtually non-existent. I wanted to just pass the lady some money out of the window and take care of the situation, but without really understanding what was going on, I was afraid of the problems this might cause.

The driver then has one of the bags of rice put back on the roof, and we drive away. Wayne, the other EWBer I was travelling with, and I just look at each other in shock. A girl in the seat behind us leans over and explains what happened. The driver was demanding an additional GHC 3 for the transport of each bag than what was originally agreed upon. The lady did not have this money, so the driver took the bag of rice, was going to sell it, and then she would have to to arrange to meet him and collect the change. A bag of rice goes for GHC 20. I hope that she was able to eventually meet him and collect her GHC 17, as that was probably her month’s income.

White Privilege

Another overcrowded tro: people sitting on people. They say I should get in. Wanted to buy bananas still, but didn’t want to miss this opportunity to go to Lawra, especially after my last misadventure trying to get home.

Sigh, it will be a long ride back to Lawra. I’m about to climb in and they grab me and tell me that no, I am to sit in the front.

The sun is still high in the blue, clear sky. I figure it will be a tad safer than the last time I rode in the front. Definitely a little more breathing space than in the back.

We’re off almost immediately, and the driver is driving safe and respectably.

As we pass through some customs checkpoints, I can’t help but wonder if the drivers often strategically place me in the front of the tro so they will just be waved through these checkpoints and avoid inspection.

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Left to Right

Mariko, my office mate, put a world map up on our office wall today. Africa, Europe and Asia are on the left hand side of the map. I’m used to seeing world maps with the Americas on the left hand side. Seeing the world unraveled this way for some reason makes Canada and Ghana look really, really, really far apart.

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

French Toast

Succumbed and addicted. Knowing this was a weakness of mine, I tried to resist making it, but alas. French toast is helping me deal with sugar (and cake) cravings. Vanilla, orange zest, cinnamon, sugar and condensed milk are mixed with the eggs. Honey or jam on top.

A perhaps slightly better alternative is oatmeal laced with sugar and jam, and when I’ve recently returned from Wa, apple chunks. Helps with the sugar cravings, but not the cake cravings.

Happy tummy = happy girl.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

In Unexpected Ways

I have now been in Ghana over a month. This past weekend I was in Wa again. This time, however, I was alone. One lone nansala (white person) wondering around the city. I was trying to find a particular store and turned down one street. After walking for a few minutes I realized that I was on the wrong street. It was hot. Really, really hot. I didn’t want to backtrack, so I turned down a side street. I figured that since the street I was on, and the street I wanted to be on ran at 30 degrees from each other, this perpendicular street would eventually take me to where I wanted to be. This side street ended up not being a direct route, but rather a winding path through a residential area. However, I kept going, following two women who looked like they were headed to market (when in doubt in Africa, follow women who look like they’re going to market, you’ll usually end up where you want to be). After a couple of minutes I smiled to myself, realizing how 4 weeks ago I was uncomfortable walking down the main street in Tamale, with friends, and now I had the confidence to follow two women through an unknown residential area to where I wanted to go. (Note: mid afternoon, broad daylight, busy area, lots of mosques, it was safe, don’t worry parents/grandparents).

I find myself often thinking about how I will change from my time as a JF. And to be honest, I don’t know what I will take away from my time in Africa. I often feel like because I am not swept away by same passionate idealism, “got to save the world” attitude, that seems to consume many JFs that have come before me, that maybe I don’t quite fit this program. However, I chose to be here, because I do want to help build skill and expand perspectives of others within the global community. And, as one of my JF colleagues pointed out, they chose me over other applicants. In my own way, yes I fit.

As the expression goes, “you are the sum of your experiences”, and therefore, I am just going to assume that being in Ghana is helping to shape me the way that I need to be shaped, to do what I need to do later in life.

Before I came to overseas I spent the last year consulting for big oil. I learned about the industry, the challenges of managing field operations, the intricacies of corporate communications and more about SAP than I ever wanted to know. During my first week in Ghana I was overwhelmed by the changes in my physical surroundings. I’ve barely even camped in my life, and here I was living without electricity, water or toilet and surrounded by more bugs and animals than I was comfortable with. Nearly in tears while trying to come up with a good excuse to jump on the next plane to Canada, I had the I suddenly had the thought: “What would the [super-field] boys do?” I don’t know where this thought came from, but I knew what they would do. They would be ok; more than ok. And somehow, because I knew this, I knew that I too could be ok. When I left this job, I thought I knew what I was taking away. What I didn’t realize was that I was taking away the confidence and encouragement I needed to make it through my first couple of weeks in Africa.

Earlier this week while biking down a side road to visit my first home here, I realized how much the road had changed since I had last passed down it a few weeks ago. The millet was now 10 feet tall, the path was slightly different, the trees were greener. This led me to think about how I had changed in the short time I’ve been here. First off, I once thought those millet plants were maize, and now I can confidently type them as millet. But are also inward, and perhaps more important, examples of this change. I see myself becoming more accepting and adopting of the openness of Ghanaian culture; I greet more and more people I pass on the streets each day. I have a deeper gratitude for everything I have back in Canada, a greater appreciation for all the education that I have received and a deeper desire to do something with it.

A friend of mine who spent 18 months living in Africa shared the following:

“ … all the things that we just got used to that we thought we never could and then we came home and it was SO weird to be home. Way weirder than going. Weirder because you think that when you come home, you are going to be fine and then you aren’t. You are different from being somewhere else … in a way you don’t realize.”

It is likely then that the things I think I am learning right now are not going to be the ones that have the greatest impact on me in 3 months when I return to Canada, or in 3 or even 30 years. Thus, instead of worrying about how I am growing, and what I can take away from this experience, I think that should just enjoy my experience, be here and live these next three months the best I can. And then, when I draw upon my collective experiences to make a decision or face a particular challenge, I can perhaps recognize some of the lessons learned and character that was built in Ghana.

Monday, September 14, 2009

Agriculture Extension Services

This post is intended to give you a little better understanding about Agriculture Extension Services in Ghana. It is by no means comprehensive, but hopefully it is mostly correct. Then again, it’s based on the observations of somebody who up until 43 days ago, knew practically nothing about agriculture. Nevertheless …

***

The concept of Agricultural Extension Services was originally conceived as a method to “extend” research-based knowledge to rural sector, which would not typically have access to this information. This knowledge could include things such as technology transfer, business and agro-marketing skills, non-formal education, or development projects - anything to improve the livelihood of agriculturally-based communities.

Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs) form the heart of MoFA’s Extension Program. The AEA is link between MoFA, its research, programs, and technologies and the farmer. Some of the responsibilities of the AEA include:

- Administration of subsidy programs (e.g. distributing and tracking fertilizer subsidy coupons), coordination of demonstration farms block farms and farmer field schools

- Dissemination of technology and messages from MoFA to farmers

- Monitoring and reporting of environmental conditions in their regions

- Monitoring and reporting of farmer’s successes, challenges and failures

- Facilitation of relationships between farmers and farmers groups, and helping them to develop market linkages

- Working directly with farmers to help them to find the appropriate solutions and resources to overcome any potential challenges and maximize opportunity for growth and improved livelihoods.

Farmer Field Schools (FFS) exist to give communities of farmers the opportunity to come together regularly, receive important information, and ideally, share the challenges they are facing and learn from each other.

Communities of farmers meet with their AEA on a regular basis in a community location. Their field school location is often near a demo or group plot on which they can practice techniques learned. Field schools also serve as a forum for experts or visitors to come in and share specific messages with the farmers. For example, during August, FFSs were held in the Lawra District on proper application of fertilizers and energy saving farming techniques. Farmers were reminded of how to use fertilizer backpack sprayers, proper maintenance of equipment, appropriate concentrations (dilute by volume, not by taste) and the importance of using personal protective equipment. Each school was provided with some more equipment (a couple of pairs of Wellingtons, and another backpack sprayer) to be shared in their community. This session also spent time discussing energy saving farming techniques. During the farming season, and in particular, during weeding time, the regional food supply is at its lowest. The instructor was teaching them different stroke techniques, how to get the weeds out without massive labor to conserve energy, reminding them of the ease of using full length handles, instead of just short hoes (which require you to be continually bent over), and the importance of removing the dirt from the roots, so that they will dry up and not replant themselves. While I see the importance of these messages, I was surprised that these were the types of messages that had to be shared formally, and that there was some even skepticism regarding some of them. I don’t even really know what an appropriate comment or speculation might be. I spent a summer clearing my parents’ acreage by hand, and quickly figured out and adopted energy saving and labor-reducing techniques. I can’t even imagine diluting fertilizer solutions by taste. Why these messages need to be shared? Lack of education? No motivation to improve techniques because their livelihoods seem to never change? This one puzzles me.

AEAs, as they are the government employee that has the closest relationship with the rural community, are also often tasked with sharing information on “cross-cutting” themes, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and water and sanitation. These factors have a large impact on agricultural productivity, and so are often included as part of extension messages.

As previously noted, farmer field schools sometimes (ideally) have a small piece of land with their “school” location. This land can be used to address questions, or design crop experiments, based on challenges that they may be experiencing in the area. The role of the AEA here is to help encourage the farmers to come up with the right questions, and right experiments to design.

Demonstration Plots are coordinated by AEAs to help share a new crop or technique with a community. The land for a demonstration plot is donated by a farmer who the AEA has chosen to be one of the community “contact farmers”. In choosing who to work with AEAs typically look for someone who has shown independent innovation and initiative in improving their own farm. The contact farmer should also be someone who is respected within the community, someone community members would turn to for advice. The plot should typically be in a location that will be noticed by others (near a road, common pathway, etc.) not in the farthest, most distant corner of the land the farmer owns.

The ideas for demo plots come 1) centrally from MoFA, 2) from partnerships with NGO projects and sometimes, 3) from the community or AEAs themselves. The AEA will work with the contact farmer to get the demo plot set up, and then the farmers will incorporate the management of the plot into their regular activities. The AEA may bring members of his FFSs to see the plot, with the hopes that they will in turn, talk to the contact farmer about it to learn more from their peer, or actually just go ahead and adopt the practices themselves.

I’ve seen many demo plots while I’ve been here: specific varieties, no-tillage, varied fertilizer application, use of compost, etc. One highlight was when we visited a composting demo. The differences in the control crops and those that had compost added to the soil were amazing. Moreover, the contact farmer informed us that he had then gone and added compost to the rest of his crops, and everything was doing amazing. Adoption in action! On the other end of the spectrum, we were visiting a farmer in another area who had a groundnut demo of some sort (I don’t really remember what it was about). He took us on a 20 minute hike, winding back further and further from houses, roads and crops. He never got around to planting the demo, and so ran out of land. Furthermore, only half of it was planted to specification, the half looked like seed was just haphazardly thrown to the ground.

MoFA also currently uses “Block Farms” as a loan mechanism to help farmers access the necessary inputs. The community must first find land to use for the block farm. A block farm is typically 20 -40 acres, and the land is usually donated by one of the profitable farmers in the community. Members of the block farm are chosen by the community. In order to be part of this farming activity, the member must commit to contributing equally to the plot of land. It is important that participation is decided upon by the community, as opposed to the AEA choosing who should participate. This way, if there are any problems with member not contributing adequately, it is something that the block farm members must deal with on their own. Once the area and members have been established, if required, MoFA will lend their tractors to till the land. Seeds, and as needed, pesticides and fertilizers, are then “loaned” to the farm. At the end of the season, the cost of these inputs must be then paid back to MoFA out of the crop yields.

There are two approaches to the management of the farm area. Each individual will be solely responsible for their own 1-2 acre parcel. They will sow, weed and harvest their own area and is will receive the profits only from their parcel. Alternatively, the community can come together and work the entire block farm. The yield and profits will then be divided up accordingly. Irrespective of which method is used, the ideal approach is that everyone will be working in the field at approximately the same time. As a block farm is essentially one large farm, of a homogenous crop, it is important that fertilizers and pesticides are applied uniformly across the entire area.

I feel that I have only provided a small glimpse into what agricultural extension services are about in Northern Ghana, based on what I have observed over my first month working here. While I am still seeking to understand extension more fully, many challenges that are faced by MoFA staff have become very evident. There are many messages and potential technologies/techniques that need to be disseminated. While some of these are decided on at the district or regional level, based on need, many still are passed on from Accra. With limited time and resources, it is often necessary to choose what is relevant and appropriate. Sometimes the right messages make it to the farmers, and sometimes, well, their relevance may be lost on the farmers, not necessarily because of ignorance, but because they are simply wrong for that particular community. I have also seen that literacy is a problem for some areas of extension. Labels on inputs are in English; many farmers cannot read English. There is always a translator available for FFSs, but what happens when you leave the farmer’s with a bottle of fertilizer and they forget what they learned? They dilute to taste. Beyond that, some can’t even read their local language, and this creates other problems. I was with some officers when we were delivering fertilizer in exchange for some crop as payment. They wrote down what they had delivered, and taken, but had to have the farmer manually count at each bag and bottle and help him understand where the numbers were on the record of transaction. They spent some time doing this, and I’m not entirely sure he got it, or even cared that there was a record. However, I was told that this record was important, because quite often they will come back and say the right quantities were not delivered, when they fail to have the expected outputs at the end of the season.

If you ask an AEA what his biggest challenge is, he (or she, I’ve met a couple of awesome female AEAs too) will say time, fuel and motos. Often they want to go out to a particular area for a follow-up visit, or to help specific activities, but don’t have enough allowance to cover the needed fuel, their moto is in poor repair, or their area is too large to cover. There are some complaints (and substantiating stories) that AEAs are not motivated, and only do the minimum. However, all the AEAs I’ve had the opportunity to work with are clearly here because they love their job, community and agriculture.

“I come from a long line of farmers so you could say farming is in my blood. That’s why I love working at MoFA. I was lucky to be able to go to Agric College, and so I want to share my knowledge with others. I love going out into the community and talking to the farmers and learning their challenges and trying to figure out ways to help them. I can’t fix all their problems, but I can try and help as much as I can. I also like trying to get farmers talking to each other and working together. ” – One of my favorite AEAs, (and therefore I’ll keep him anonymous), Lawra District, Upper West Region

A Farmer Field School

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Samuel Saakuu Baaru

One of the first people I met in Lawra was Samuel Saakuu Baaru. Sam opened up his home to me, and gave me a great introduction to life in Ghana. When I asked him if I could include him in my blog, he quickly agreed, most likely thinking of international exposure for his xylophone business.

Sam is the manager of Baaru and Sons Xylophone Learning and Training Centre. This family business has been operating for more than twenty years. Initially just operating as a production centre, it has now been converted to a training centre, training youth in traditional trades and music, providing skills for potential employment and contributing to the preservation of tradition. The success the centre is part due to community based and rural development projects, but also very evidently the passion Sam has for his trade and Ghanaian culture. In Ghana, xylophones are an integral part of many traditional activities including funerals, festivals, church and school activities.

His work has been featured at numerous trade shows, supported by the Ghana Export Promotion Council and the National Board for Small-Scale Industries. This has earned him the requisite recognition required for both local and international markets. The materials that go into each xylophone are grown or produced locally, either in Ghana or Burkina Faso, and hand-selected by Sam or one of his trained craftsmen.

The first ten days of the training program are used for studying the theoretical aspects of xylophone music, xylophone tradition and construction techniques. The next ten days are used for learning construction techniques, with 35 days then spent on practice. At the end of the training there are five days of individual construction evaluation. At the end of the training program, participants will be able to construct xylophones to the standards set by Sam’s centre. He has spent the last couple of weeks putting together grant applications to securing funding for another round of training.

In addition to running his business and training program , Sam is a volunteer teacher with the National Literacy Program, running evening courses to teach members of his community to read and write Dagaare, the local language. I know Sam throws a little English and basic math thrown into his courses to round out their education. Sam is involved in his church, supporting their work, and community and giving back continuously through time and labor.

While living at Sam’s house, his generosity and love for his community became quickly evident. Meals were always shared with people stopping by, employees, neighbors. Quite often I would catch Sam acting as a bank for women the community, lending money so they could subsist until they were able to sell goods at Market Day.

Like many Ghanaians, Sam has been hoping to attend to university for some years now. He was finally granted admission, and will be starting Agric College next week. Having used a large portion of his university money last year to build a new workshop, he was left scrambling to find additional finds to cover his fees. His sister, Diana, is also returning to school this fall, and thus she was also looking for funds. Together, they started finding, killing, smoking and selling pork. Sam also has taken on many small projects. They both came up with the money needed for their fees.

The motto of the xylophone centre is “Sky’s the Limit”. Sam’s attitude towards life definitely exemplifies this. I’ve learned so much from him, and will miss our conversations and weekend excursions while he is away at school. However, I’m very happy and excited for him that he has finally gotten the opportunity to attend university and wish him the best of luck in his studies!

p.s. Although a little expensive, Sam has successfully shipped xylophones as far as Argentina. So, if you happen to be a collector of traditional and hand-crafted musical instruments, consider a Ghanaian xylophone as your next purchase.

Friday, September 11, 2009

Feeling Like Bruce

I’ve been here for just over one month now and all I can think about for the past week is how much I just want some cake. Well, my thoughts go back and forth between the lack of internet and baked goods/sugar. In the morning it starts out as fruit and yoghurt cravings (last night I dreamed about apples), but usually by early afternoon by thoughts are entirely consumed with visions of chocolate cake, cinnamon buns, sugar cookies, Nestle products and tubs of Betty Crocker frosting. I’ve heard rumors that when you abstain from sugar long enough the cravings go away eventually. However, I don’t believe them, this just gets worse every day.

I guess I can take comfort in the fact that we fly back to Canada via Frankfurt and I know where the airport bakery is. That way I can start my eating en route to Canada, easing my way into what will be a full on binge during the 2009 Christmas baking season.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Sew, What Shall I do Tonight?

My plan was to go into town this evening and use the internet. After bugging him for a couple of days in a row, the owner promised me he’d buy more credits and have it back up and running by 3:30pm or 4:00pm today. I planned on heading in right after work, spend a two hours there, and then enjoy a relaxing and happy evening, knowing I’d sent out a million email and hopefully uploaded a few posts. Unfortunately, my plans were foiled by yet another giant rain storm. So, I decide to venture in after dinner instead; I start my trek into town around 6:40pm. It is just about dark by this time, and I don’t like being outside in Africa (or anywhere, for that matter), after dark. This must tell you how much I really wanted to use the internet. I’ve been without cell phone (my town ran out of phone cards last Thursday, the supplier still hasn’t come) or internet for a week! After almost hitting a couple of people (dark people wearing dark clothes are hard to see in the dark!), I arrive at the Business Centre only to see that he had closed up shop early. Darn that rain! Everything closes in Africa when it rains. Sigh, I rode into town for nothing. I contemplate do a bit of shopping, but realize I am quite deflated and just head home.

As I venture down the road and get closer to where I think my apartment complex is, I realize I can’t find the path from the road to my building. Did I miss it? Is it further up the road? No one was home, so there were no lights on: I could only sort of see the building.

I scan the ground with my flashlight (whose batteries were dying, of course) and decide to off-road it. Somehow I manage to make it back to the building. My mountain bike skills are definitely coming along very nicely!

Once safely inside I realize it’s only 7:10 pm. Now what? I don’t really feel like watching a movie or reading, so I look around my apartment. Nope, nothing to do. Nothing (good) to eat. I need to do something! I decide to make hot pads. We (I share my neighbor’s kitchen, I don’t actually have one) don’t really have anything in our kitchen that is useful for lifting hot pots. Fortunately, I happen to have a small stash of fabric in my apartment. With a few scraps, a Swiss Army knife (note to self: buy scissors) and a small sewing kit, I begin my evening fun.

Two hours later, and after a couple of good laughs about at what I was actually doing, I have a beautiful pair of hand-crafted hot pads.

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Weekend Adventures

August 22 – The Black Volta

The Black Volta marks the border between Lawra District (Ghana) and Burkina Faso. I didn’t realize I was only about 3 km from another country. Depending on the way the wind is blowing, some days my cell jumps onto the Burkina cell networks, causing me all sorts of trouble, and now I know why. Many traders come across the river for Lawra market day to access a bigger market.

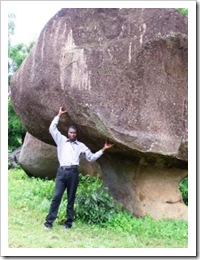

September 5 – The Mushroom Rocks and Sacred Spring

South of Lawra there is an area known as the Mushroom Rocks. From the pictures, it is pretty self explanatory. It almost felt like we were in a prehistoric area with random rock formations cropping up out of seemingly nowhere. I also enjoyed photographing one of the young boys who was there hanging out with his friends. He seemed to be a natural poser, and definitely loved getting his picture taken. On our way there, the moto got a flat tire. So, while Sam patched it up, I helped some ladies shell groundnuts. They are a machine! When we left, I’d probably shelled a fraction of what they did, and had very sore fingers.

Afterwards we journeyed to the Sacred Spring, which is near Babilile. Here, the ground is pretty swampy as groundwater seems up through what seems like every rock. I was told that sacrifices and rituals were often performed here, because the abundance of water was like a gift from the Gods.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Photos For Previous Posts

Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like I will be able to prepare my re-posts before I have the internet once again. A couple of the folders (namely all the ones I accessed on the public computer) on my USB got viruses, so I just let my anti-virus software eat them, instead of trying to extract the needed documents. Unfortunately, it means I sacrificed a couple of work files as well, but alas - guess I’ll be busy this week.

Thus, this post will be a little photo gallery to accompany the previous posts. If you can’t remember what the stories were about, or skipped something, this is my indirect way of encouraging you to go back and read or re-read.

Left: My two shampoo options. When I was in Wa this weekend, I noticed that in a few saloon windows there was shampoo. When (if) I run out, I might venture back and see what salon goodies I can find.

Above: I had a pretty pretty pink office (L) for the first month I was here. The, the ceiling fell in part of the building so we had to do an office reorg. The volunteers were moved to another office down the hall, so as to give the pink office to someone else. A Crate & Barrel Box (R) I found in my closet when cleaning it out. I left it in there, so I can look at it and smile if I ever get homesick at work.

Left: Some of the staff at my office. L to R, Elizabeth (typist), Asana (Administrator), Director Ojingo Onyobie Ayo (Director of MoFA Lawra District), Spencer (former EWB Volunteer), Karimu (DAO in charge of extension), Felicia (statistics recorder for fisheries), Mariko (JICA Volunteer), and Me. The other Elizabeth and I have taken to just calling each other “Name”, rather than Elizabeth.

In my new white office. With the new office we each got our own desk (I share with Mariko). Well … we do have to share with a few others, but they are not in the office regularly, so I essentially have my own desk. What is more exciting is that the power outlet in this office works so I can charge things while sitting at my desk! Now, if only we had internet …

Below: Belinda (girl on the right, in the white dress). The photo on the left is a copy of her traditional/formal portrait she gave me. Ghanaians take photos very seriously, it is hard to convince them to smile on the camera, unless you can get a completely candid shot.

Below: Sondra.

After being away for the weekend I was enthusiastically greeted by not only her, but all the children in the neighbourhood. As soon I stepped off the tro-tro (sketchy intercity transport, you question how it is still functioning/held together, but somehow you end up making it from point A to B), they pulled all the bags from my hands and carried them to my room for me.

Right: A picture of me (just in case you forgot what I looked like), trying to figure out what to do now that the sun has gone down. Fortunately, I’ve started to adapt to Ghanaian lifestyle, meaning, that as soon as the sun goes down I start to get tired. This probably has something to do with the fact that we get up, or, rather, everyone else gets up and is very noisy, thereby waking me up, before 5 am. I often opt to lay in bed and doze or listen to music or read, until a much more reasonable time of 6 am. On occasion, I’ll go for a run in the morning, but I prefer to leave work a little early and go for a run quickly before the mosquitoes come out. After you go for a run in Africa, you continue to actively sweat for at least another hour or two, despite having a cold bath. Thus, I prefer to experience this at home in the evening, rather than at work. Although, looking through my photos, I realized that something I enjoy doing is taking pictures of the sunsets, and attempting to take pictures of the moon (still figuring out my new camera, and living sans tripod). To the west of where I live is all maize fields. I think I would have to hike pretty far to get a photo of the sun not setting over a maize field, so here are a few maize sunsets and moon pictures. Every evening is unique and beautiful in its own way.

Moving Day

The big day has arrived, moving day. I have spent the last month looking for the “perfect” place to move to. I did not find this place, but a room opened up at one of the cheaper guesthouses in town. And so I’m moving. I feel very fortunate that I have been able to retain my health while living in the bush, but my body is starting to feel like it’s being pushed. I also am really missing electricity, and the ability to be productive after sundown. However, I am also sad to be leaving. I’m not moving that far away, it’s only about a 12 minute bike ride, but it really is like moving to a whole new world in some regards.

Things I will miss about Sam’s place:

- Daily conversations with Sam

- Sam’s mother’s cooking

- The neighbour kids

- The bike ride to/from work through farms

- Sunsets over the maize fields

Things I am looking forward to experiencing at my new place:

- Running water (shower!) and a toilet

- New neighbours and friends

- Working at night if I need/want to

- Cooking for myself

- Being closer to town/work

- Not being woken up roosters and goats

Although I am every excited to have my own place, I am very thankful for the opportunity I had to live with a family, and experience rural life. It probably made my initial adjustment period to living in Ghana a little harder and longer, but I think it helped to build my understanding of and appreciation for the people who live here and face the challenges of inadequate water, sanitation and food on a daily basis. I have also learned to have faith in my abilities to adapt to new circumstances.

So, time for another tour:

Below: (L) My bed, and more importantly, a ceiling fan above the bed! (R) My dresser and mirror.

Left: Desk, which doubles as my pantry. I seem to only have one working outlet in the place, but one is really all I need!

Below: (L) My clothes closet, for the things I want to hang. (R) My housewarming present to self. An electric iron! I’ve never been so excited to iron. Strange how the things we hate become something to be excited about.

Below: (L) The closet. (R) MY BATHROOM!!!! YAY!!!

My new place has no cooking facilities, but I am lucky to have Adam, the Peace Corps volunteer in town, staying a few doors down. He’s built himself a nice little kitchen, and has opened it to me to use as much as I please. Yay!

Below, the first meal I cooked myself: vegetables that were cooked just enough to sterilize them and gari with lime and ginger.

My Bike: I would also like to introduce you to my bike, Silver Spiney, aka Mr. Spiney. He is amazing. At first I was skeptical of his abilities to handle the roughed-up Ghanaian dirt roads, but he seems to be capable of many things despite being of urban, Asian-esque blood. The roads here, especially after a rain storm, are worthy of a proper mountain bike, however, Mr. Spiney’s resilience continues to amaze me. One important trick I’ve learned is that when you see a water-filled crater, do not slow do. If possible, gain speed and coast through as fast as possible. If you slow down and try to carefully navigate through, you will sink into the soil and tip, often landing with one foot in the puddle. This is then followed by immediate thoughts of Guniea worms and other parasites!

Ghanaians sometimes look at me funny as I seem to ride a lot faster than they do. I think, however, if you’re on a bike, it’s for efficiency, and so I try to be efficient. I’ve also learned how to jump curbs on it, again, getting a few strange looks, but alas. I still struggle, however, to ride it wearing long skirts, and sometimes end up hiking it up and/or riding the bike slowly/properly. I’m a little better than I used to be, but still have a long way to go. In speaking with my friend Becky today about it (met her on the road from market, she was riding wearing a long skirt while riding her bike), she says that you just get used to it. I hope so.

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

The Tastes of Ghana

For those who were worried that I would come back skin and bones, fear not, I’ll be hitting the gym on January 1 with the rest of North America. The diet here is carb-heavy, and all food is served in large portions. My attempts to eat “small-small” are futile, as my host family is convinced I don’t enough and practically force feeds me and then sometimes I am just plain hungry. Fortunately, I actually like, or at least can tolerate most foods, speaking from both my stomach and palate. The only things I’ve come across that I cannot make myself eat is fish and goat. Mystery meat is something else that scares me, so for the most part, I just avoid meat, occasionally eating various fowl if it recognizably looks like a bird. I still also struggle with the concept of eating with my hands. If my family is not around, and if I can find one, I sometimes grab a spoon to finish off my food that way.

Beverages: Most people don’t have a fridge, so I’ve become accustomed to drinking warm things. I save the chilled sodas for when I eat out as it doubles their value as a special treat.

Drinking water here is a no-no. I purchase Pure Water, which is filtered to some degree. A 500-mL satchel goes for 5 pesewas, and can be purchased pretty much anyway. In markets you may sometimes see individuals selling clear bags of water. There is plenty of juice to be found, most is actually pure juice, and made in Ghana. The only downside is juice is expensive, but entirely worth every cedi spent on it. My favorite find is soy milk, natural and chocolate flavor. Always looking for protein alternatives ….

Doughy Ball Things: This pretty much describes most Ghanaian food. Below you will see me attempting to pound yams and cassava into fufu, which is then displayed on the right. Below the fufu is kenkey, which is fermented maize-based dough, served with fish and light soup. Definitely not my favorite. On the bottom left is Bo Froote, which is essentially a doughnut, and a staple in bus yards. I think they’d be fantastic rolled in sugar and cinnamon, but I have yet to find some cinnamon in this country.

Below left is tuo zafi (commonly called TZ), which is millet or maize porridge cooked until it is stiff and doughy, and a staple of many of the poorer families. On the right is a bean cake. I was surprised how good pounded and mashed and rolled up beans were, but possibly this delight was due to the fact that I knew this one was a little more than just carbs. I don’t have a picture of banku, but it is another fermented dough creation, served with a soup/stew as well.

Rice and Beans: I am very grateful for the presence of rice and beans in the Ghanaian diet. Even in Canada, they are two of my favourite foods, and I often eat them combined as they do here. I have also discovered gari (dried and ground cassava), which is the Ghanaian equivalent of farofa. On the right, you’ll see some fried plantains. I’ve never been a huge plantain fan, but the ones served here (again, cooked by my host mother), were actually pretty tasty!

Stews: Various stews of tomatoes and leaves, are often served over rice, or to accompany TZ, or just because. Most are pretty good (if they are fish free, that is), especially the ones my host mother makes. Everything is Ghana is well cooked to mush, but the previous volunteer taught our mother about leaving chunks of vegetables. On occasion we will have chunks of mushy vegetables instead of just completely mushed vegetables in the stews. Again, another surprising delight.

Breakfast Items: I never thought I’d be dreaming of cold cereal, but I alas, I have begun to. I did see a box of Corn Flakes in a store in town, but I’m scared to see how much they cost, and well, I’m not really a corn flakes fan. Exhibit A below on the left is a bag of coco. Coco is the morning porridge, and when purchased to go on the street, comes served in a bag as such. You bite off the corner and suck away. Eating from a bowl with a spoon is much more pleasant. Some people put ginger in their coco, which is actually quite good. I can barely finish 2000 worth of coco (20 pesewas, or approximately $0.16 CDN). On the right you’ll see a groundnut butter and honey sandwich. This is one of the breakfast staples in my house. When there are bananas, we’ll add them as well. I’ve even had a fried egg thrown in the sandwich from time to time (not super great, but protein, so I won’t complain). However, Sam, once he realized that I’ll usually only eat one sandwich (because it is quite often accompanied by a bowl of coco), started making mine bigger and bigger.

Exhibit C to the left is Sarah breaking her hard-boiled egg on the roof of the bus. Next to this is exhibit D, a little fuzzy, but it is egg and bread, which is essentially an omelet fried into bread. This is definitely the best breakfast Ghana has to offer.

Meat: I’m not a huge fan of eating meat here. Every little bit of an animal used, and so you don’t really know what you are eating. On the left is fried chicken. This chicken was one that was wandering around my yard in the morning, by mid afternoon she was chopped up in a bowl, and then in the evening she was sitting on that plate. And no, I did not take part in the butchering and plucking process. On the right below is a pig being smoked. Again, this pig was alive in the morning (although not in my yard), then smoked by Sam and his gang, and then wound up in my stew later that evening. There were a few pieces that I couldn’t recognize, and therefore didn’t touch, but then there were a few good pieces that were clearly just hunks of smoked pork that enjoyed more than I imagined, as they were my first pieces of meat in quite some time. When eating out, a lot of food vendors will have hard-boiled eggs available as a nice alternative to meat. One interesting note is that I’ve never heard the term beef used here, instead, they just refer to it as cow meat. Probably because it is quite literally just a random hunk of cow they are giving you.

Special Treats and Snacks: Italia, aka pasta, is a great treat to have here. Of course, it seems to be always served with rice, just in case a giant plate of pasta wasn’t enough for you to eat and absorb. The plate below was what was served to me for lunch. It was plenty (considering I’d be having a plate of something just that large for dinner), but it was delicious. You’ll notice there are even chunks of carrots in the pasta. Definitely a special treat! On the right is chocolate paste I discovered on my quest to find something sweet one afternoon. It is actually Brazilian Ducremo, so not the best chocolate treat one could have (I’m not a huge fan of Brazilian chocolate treats), but smeared over a digestive cookie, it was delicious. (Starting to feel the effects of chocolate deprivation one month in, good thing I’m coming home just in time for Christmas … hint, hint). The little round balls in the bottom right are, as far as I can tell, just dried or baked balls of ground nut paste and maybe some flour. They do resemble dried dog food in smell and texture, but soften up after being in your mouth for 20 seconds so you can chew through them. A store in town just started stocking Laughing Cow Cheese. The owner was very excited about it, and has made sure to tell all the Nansalas (whites) in town. I guess he knows how much we love our cheese. It is really cheap too, only 2 cedis!

Mangoes: Sadly, I arrived just at the end of the mango season, so I only got to enjoy a couple of mangoes while in Tamale. And yes, did I ever enjoy them. I think that I still prefer Pakistani mangoes, but Ghanaian mangoes come in a close second. If was here earlier in the season, and would have been able to pick them off the tree myself, they might have made it into first place. The Mango Tree also seems to be a very important part of Ghanaian culture. They grow in a way to provide perfect shade, and so, more often than not, there will be several benches under the mango trees and people just hanging out. In Bole, a particular mango grove is home to a moto repair shop that gets set up daily. Even during mango season, they are scarce in the Upper West due to problems with the Mango Stone Weevil and Fruit Flies. I’m not sure to what extent this is a problem elsewhere in Ghana. From the research posters I saw at work (They study fruit flies, I kid you not!), there are ways to combat and/or manage this, but as always in Africa, more resources are needed to actually do so. I’ve included snapshots of the research posters for you science folks.

Grocery Shopping:

Fruits and vegetables are purchased at the market. Bread, canned and boxed goods can be purchased from any number of small stores in town. Sometimes I think about the grocery stores in Canada, and even get a little misty eyed. We can get anything we want, in pretty much any season if we are willing to pay. I often wonder what a village Ghanaian would think if they were to enter Sobey’s or Loblaw’s. And as for me, I can’t wait to go grocery shopping in December.